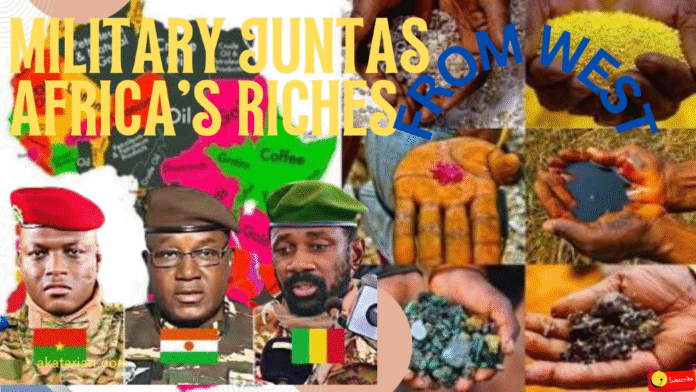

From Ouagadougou to the Amazon, a new generation resists an old playbook of plunder disguised as partnership. But as a young leader in Burkina Faso is painted a villain, can the continent finally break free from the puppeteers of power?

The atmosphere in Ouagadougou is tense and filled with a mix of defiance and worry. Captain Ibrahim Traoré, the young military leader who seized power in Burkina Faso in 2022, is the latest African figure to find himself in the crosshairs of Western powers. The narrative, echoing familiar scripts, is taking shape: whispers from Washington, amplified by international media, suggest Traoré is illicitly using the nation’s gold wealth not for its people, but to bolster his personal security and cling to power.

From my vantage point in the diaspora, watching this unfold feels like a grim déjà vu. We have seen this play before, where African leaders who dare to assert true sovereignty over their resources or chart a course independent of Western diktats are systematically undermined, demonized, and often, overthrown. Is Traoré a saint? Perhaps not. But the critical question, the one often drowned out by the chorus of “concern” from abroad, is this: who truly benefits when an African leader demanding control of his nation’s wealth is targeted? And is this “concern” genuine, or merely the latest smokescreen for an age-old agenda of exploitation?

This is a global saga of how powerful nations, cloaked in the rhetoric of aid, democracy, and human rights, have historically manipulated, destabilized, and plundered weaker nations for their riches. The script, refined over decades, plays out with chilling consistency, whether in the mineral-rich soils of Africa or the fertile lands of South America.

The Shadow of Intervention: A Global Pattern

Before we dig deeper into Africa’s modern wounds, let us not forget the precedents set elsewhere. The United States, often with its allies, has a long and storied history of intervention, particularly in South America, where the Monroe Doctrine laid an early claim to regional dominance.

Guatemala (1954):

When President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán dared to implement land reforms that threatened the interests of the powerful U.S.-based United Fruit Company, he was swiftly overthrown in a CIA-backed coup. His ousting ushered in decades of civil war and brutal military dictatorships. Árbenz himself lamented, “They have used the pretext of anti-communism. The truth is very different. The truth is to be found in the financial interests of the fruit company and the other U.S. monopolies which have invested great amounts of money in Latin America and fear that the example of Guatemala would be followed by other Latin countries.”

Brazil (1964):

President Joao Goulart, who pursued nationalist policies including land reform and sought to limit profit expatriation by multinational corporations, was toppled in a military coup openly supported by the United States. Washington’s rationale was that Goulart was leaning too far left. The result? Two decades of oppressive military rule.

Chile (1973):

The democratically elected socialist President Salvador Allende nationalized the copper industry, a move that directly challenged American corporate interests. A U.S.-backed coup led by General Augusto Pinochet ended Allende’s government and his life, ushering in a brutal dictatorship that tortured and killed thousands under Pinochet. Henry Kissinger, U.S. National Security Advisor at the time, infamously stated, “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its people.” The “irresponsibility,” it seems, was daring to control their own resources.

These are not isolated incidents but calculated moves to ensure resources and political allegiance flowed in a direction favorable to Western powers. The playbook was clear: any leader prioritizing national interest over foreign corporate or geopolitical designs becomes a target.

Africa’s Open Veins: Regime Change and the Resource Curse

This very playbook has been ruthlessly applied across Africa, often with even more devastating consequences. The continent, blessed and cursed with an abundance of gold, diamonds, oil, coltan, cobalt, and uranium, has been a grand stage for this drama of dominance.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (1960s):

The charismatic Patrice Lumumba, Congo’s first democratically elected Prime Minister, envisioned a truly independent nation, free to use its immense mineral wealth for its own people. His famous independence day speech declared, “We have known harassing work, exacted in exchange for salaries which did not permit us to eat enough to drive away hunger, or to clothe ourselves, or to house ourselves decently, or to raise our children as creatures dear to us.” Such defiance was intolerable. Within months, he was deposed in a coup with documented U.S. and Belgian involvement, and subsequently assassinated. His removal paved the way for Mobutu Sese Seko, whose decades-long kleptocracy was staunchly supported by the West as a bulwark against communism, all while Congo’s riches flowed outwards.

Ghana (1966):

Kwame Nkrumah, a towering figure of Pan-Africanism, championed industrialization and sought to break neocolonial economic ties. While he was on a state visit to China and North Vietnam, he was overthrown in a military coup widely believed to have had Western intelligence backing. His vision of a united and economically independent Africa was a direct threat to established interests.

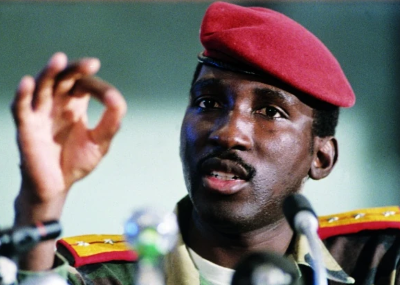

Burkina Faso (1987):

Thomas Sankara, a revolutionary leader, renamed the country from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso (Land of Incorruptible People). He implemented ambitious programs for education, health, and food self-sufficiency, and famously denounced foreign aid as a tool of control, stating, “He who feeds you, controls you.” His fiercely independent stance and anti-imperialist rhetoric made him a marked man. He was assassinated in a coup backed by powers who found his vision of self-reliance unpalatable. His words still resonate:

Our country produces enough to feed us all. We can even produce more. Alas, for lack of organization, we are forced to beg for food aid. This is an insult.

Thomas Sankara

Libya (2011):

The NATO-led intervention, with strong U.S. and French backing, overthrew Muammar Gaddafi under the banner of humanitarian intervention. Gaddafi, for all his autocratic tendencies, had used Libya’s oil wealth to achieve significant development and was proposing an African gold-backed dinar to challenge the U.S. dollar’s dominance in oil trade. The aftermath of the intervention is a catastrophic failure: a fractured nation, open slave markets, a haven for extremist groups, and its oil resources once again easily accessible to foreign corporations.

Sudan (2019):

While the removal of Omar al-Bashir was driven by what seems to be popular democratic movements, the subsequent instability and the current devastating conflict see foreign powers vying for influence and access to Sudan’s gold and strategic location. The promise of democracy has, for many, dissolved into a nightmare of renewed warfare.

The pattern is undeniable: leaders who challenge the economic status quo, who seek to nationalize resources, or who pivot away from Western patronage often find their tenures violently cut short. The “resource curse” is not inherent to the resources themselves, but a consequence of a global system that allows powerful nations to prey on weaker ones.

Congo’s Agony: A Case Study in Exploitation and Endless War

Nowhere is this tragedy more apparent than in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). For over two decades, particularly in its eastern provinces, a bloody conflict has raged, claiming millions of lives. This is not a simple tribal war; it is a war fueled by the insatiable global demand for Congo’s vast mineral wealth. Coltan for our smartphones, cobalt for our electric car batteries, gold and diamonds for our vanities.

Armed groups, often backed by neighboring states who themselves are proxies for larger international interests, terrorize local populations, forcing them to mine these minerals under horrific conditions. Weapons, often originating from or financed through complex international networks, flood the region, perpetuating the violence. Foreign corporations and shadowy middlemen are deeply implicated in this deadly trade, sourcing “conflict minerals” and turning a blind eye to the blood spilled to extract them. “They say it is our war, but we see the foreigners in their nice cars, going to the mines. The soldiers have new guns, not made in Congo,” a displaced teacher from North Kivu, who wished to remain anonymous for safety, told an underground journalist. “Our children die so the world can have its phones and its green energy. Is this fair?”

The Congolese Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Dr. Denis Mukwege, has tirelessly campaigned against this exploitation, stating, “The link between the exploitation of natural resources and the conflicts that have plagued the Congo for more than 20 years is clear to everyone. These resources, which are the happiness of some, are the source of misfortune for the Congolese people. Despite a massive UN peacekeeping mission (MONUSCO), now gradually withdrawing under pressure from a frustrated Congolese government and populace, the exploitation continues. The question lingers: if the world’s most powerful nations truly wanted to end the conflict, couldn’t they exert decisive pressure on the corporations and countries that profit from Congo’s chaos?

The Rise of Khaki: Why Military Juntas Gain Traction

Against this backdrop of perceived betrayal and failed Western-backed “democracy,” is it any wonder that military juntas are gaining popular support in parts of Africa, particularly in the Sahel? Leaders like Captain Traoré in Burkina Faso, Colonel Assimi Goïta in Mali, and General Abdourahamane Tchiani in Niger are often viewed by their populations not as tyrants, but as liberators from a corrupt political class seen as beholden to foreign interests, especially former colonial power France.

These military leaders speak a language of sovereignty, national pride, and a desire to control their own resources and security. They are severing long-standing military ties with France and other Western nations, sometimes turning to new partners like Russia, not necessarily out of ideological alignment, but in a desperate search for alternatives. “For decades, they told us democracy was the answer, but what democracy did we have? A democracy where our leaders flew to Paris for instructions, where our resources were pillaged, and where insecurity spread like wildfire,” a student activist in Niamey, Niger, commented after the 2023 coup. “If these soldiers can give us back our dignity and our country, then they have our support.” This sentiment reflects a profound trust deficit. The promises of democracy, development, and security offered by Western powers have too often translated into continued economic dependency, political instability, and the erosion of national sovereignty. Cameroon has a president who has been in power for 42 years. He is over 90 years old and needs caregivers to support him. Despite often living in Paris, France, and only visiting Cameroon occasionally, he remains the president. Cameroon is struggling, yet France does not seem to object to a leader who has held power for decades without significant development in the country simply because Paul Biya is a loyal puppet of France.

A Future Forged in Africa, By Africans

From my place in the diaspora, a child of Africa watching my ancestral home continue to be courted and coerced, the path forward, though fraught with challenges, must be one of self-determination. The accusations against Traoré in Burkina Faso, whether true or fabricated, serve as a stark reminder: any attempt to break from the established order will be met with immense pressure. The illusion of aid and benevolent partnership has shattered for many Africans. The continent is awakening, demanding to be the master of its own destiny. The spirit of Lumumba, of Sankara, of Nkrumah, is being rekindled in a new generation that refuses to be a pawn in geopolitical games or a mere supplier of raw materials for the enrichment of others. As Thomas Sankara prophetically said, “We must dare to invent the future.” That future cannot be one where Africa’s wealth continues to be a magnet for foreign exploitation and a trigger for conflict. It must be a future where the gold of Burkina Faso builds schools, not fortifies a leader against foreign-instigated threats; where the cobalt of Congo powers Congolese homes before it powers Western Teslas; and where African leaders are accountable, first and foremost, to their own people, not to external puppeteers. The road will be long and arduous. But the new scramble for Africa will only end when Africans, united and resolute, declare that the continent’s bounty is no longer for sale to the highest, or most manipulative, bidder. The world watches. And we, in the diaspora, watch with a mixture of hope, anxiety, and an unyielding belief in Africa’s ultimate rise.

Andrew Airahuobhor serves as the editor of Akatarian.