In recent years, the conversation around Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) in Canada has intensified. Once limited to those with terminal illnesses and unbearable suffering, the scope of MAID has broadened to include more categories, including mental health patients. Proponents see it as a compassionate choice to help people die with dignity. Critics, however, fear it’s a cost-saving measure veiled in empathy, potentially steering society toward dangerous ethical terrain. Some have even likened it to modern eugenics—a harsh accusation that raises concerns about how society values life, especially for the vulnerable.

This analysis unpacks both sides of the debate, exploring whether Canada’s MAID program is a humane solution or a slippery slope toward a dystopian future where life’s worth is measured in dollars.

The Legal Framework: What is MAID?

Canada’s journey with assisted dying began in earnest with the passing of Bill C-14 in 2016. The law permitted assisted dying for those whose natural death was “reasonably foreseeable.” However, Bill C-7, passed in 2021, removed the “foreseeable death” requirement, significantly expanding eligibility.

Eligibility Criteria:

To qualify for MAID, a person must:

- Be at least 18 years old.

- Be eligible for Canadian health insurance.

- Have a grievous and irremediable medical condition.

- Make a voluntary request for MAID, free from external pressure.

- Provide informed consent after considering all treatment options, including palliative care.

Two independent health professionals must assess the individual’s eligibility. The process is rigorous to ensure patients are making autonomous decisions. However, the expansion of MAID to include non-terminal conditions and, potentially, mental health issues by 2027 has sparked concerns.

Key Findings from the Fifth Annual Report on MAID (2023)

The Fifth Annual Report on MAID in Canada provides detailed data on requests, assessments, and provisions for the 2023 calendar year. Here are some of the key findings:

Total Requests and Provisions

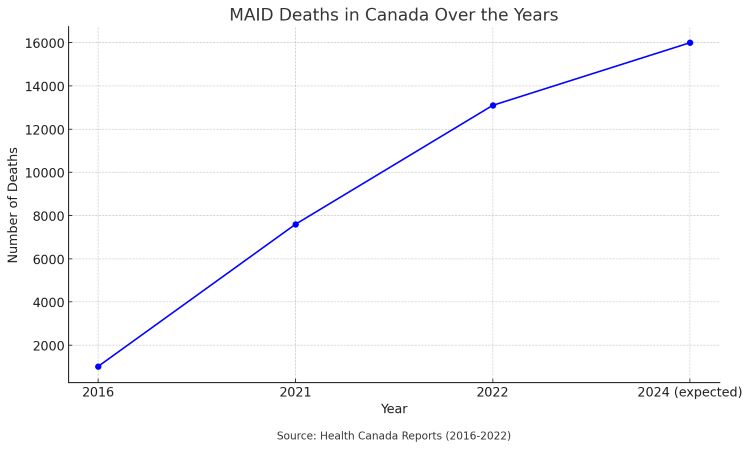

- 19,660 requests for MAID were made in 2023.

- 15,343 individuals received MAID, marking a 15.8% increase from 2022.

- 2,906 individuals died before receiving MAID.

- 915 requests were deemed ineligible, and 496 people withdrew their request.

For every five individuals who received MAID, one person could not access it before death. This shows that while access to MAID is increasing, there are still delays and barriers.

Tracks of MAID

There are two tracks for MAID based on whether a person’s death is “reasonably foreseeable”:

| Track | % of MAID Cases | Common Characteristics |

| Track 1 (Death foreseeable) | 95.9% | Older individuals, mostly with terminal illnesses like cancer. |

| Track 2 (Death not foreseeable) | 4.1% | Younger individuals, more women, often with chronic conditions like neurological diseases and disabilities. |

People in Track 2 lived longer with their conditions, with 31.8% living with their illness for over 10 years compared to 7.7% in Track 1.

Demographics of MAID Recipients

- Median Age: 77.7 years for Track 1 and 75.0 years for Track 2.

- Gender: More men received MAID under Track 1, while more women received MAID under Track 2.

- Primary Conditions:

- Track 1: Cancer (64.1%) was the most common underlying condition.

- Track 2: Neurological conditions and chronic illnesses like diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and chronic pain.

Women are more likely to seek MAID for chronic conditions under Track 2, aligning with general trends in chronic illness prevalence among women.

Racial and Cultural Identity

For the first time, the report includes self-identification data:

| Identity | % of Respondents |

| White (Caucasian) | 95.8% |

| East Asian | 1.8% |

| First Nations | 0.5% |

| Métis | 0.2% |

The majority of MAID recipients identify as White, with minimal representation from Indigenous or other ethnic groups. This raises questions about accessibility and cultural perspectives on MAID.

Disability Status

- 33.8% of MAID recipients self-identified as having a disability.

- Track 2 recipients were more likely to report having a disability (58.3% compared to 33.5% in Track 1).

- The most frequently reported disabilities were mobility-related and pain-related.

Palliative and Disability Support Services

- 75.0% of MAID recipients accessed palliative care.

- 33.8% accessed disability support services.

- Only 2.8% reported needing but not receiving palliative care.

Most individuals receiving MAID had access to palliative care, suggesting that MAID is often chosen even when traditional care options are available.

Practitioner Involvement

- There were 2,200 unique practitioners providing MAID in 2023.

- 89 practitioners accounted for over 35% of Track 1 cases and 28.6% of Track 2 cases.

Arguments in Favor of MAID

Organizations like Dying With Dignity Canada (DWDC) champion MAID as a human right. They argue that it provides autonomy and dignity to those facing unbearable suffering. According to Dr. Konia Trouton, Medical Director of West Coast Assisted Dying, MAID is a patient-driven process with stringent safeguards.

Key Points from Proponents:

- Autonomy and Choice: MAID allows individuals to control the timing and manner of their death.

- Dignity: It ensures a peaceful and painless end, reducing prolonged suffering.

- Access to Palliative Care: MAID is often accompanied by palliative care, ensuring patients explore all options.

Dr. Trouton emphasizes that the medications used in MAID, such as midazolam and propofol, ensure a calm and painless death. She refutes claims that patients experience drowning-like deaths, stating that autopsy reports have shown no such evidence.

Concerns and Criticisms

Despite the safeguards, critics like Jordan Peterson and Kelsi Sheren raise ethical and practical concerns. They argue that expanding MAID could lead to vulnerable people choosing death due to external pressures or societal neglect.

The Slippery Slope Argument

Initially, MAID was limited to those with terminal illnesses. Now, it’s available to individuals with chronic conditions and may soon extend to those with mental health issues. Critics worry that this expansion could normalize assisted dying, making it an easy solution to complex societal problems like poverty, mental illness, and lack of healthcare access.

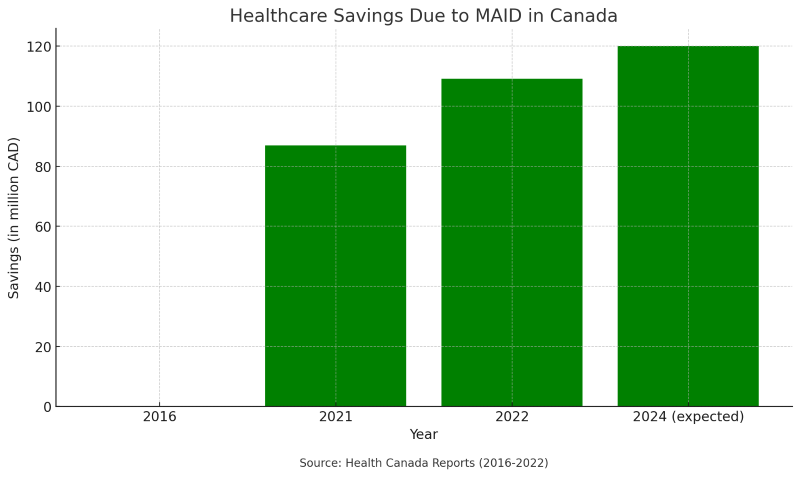

Financial Implications

One of the most controversial claims is that MAID saves the government money by reducing healthcare costs. Peterson and Sheren point to reports indicating that Canada saved millions of dollars by offering MAID instead of prolonged medical care. Critics fear this financial incentive could drive further expansions of the program, prioritizing cost savings over human life.

Vulnerable Populations at Risk

There are concerns that vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, disabled, and those with mental health issues, may feel pressured to choose MAID. Sheren recounts cases where veterans were offered MAID instead of adequate healthcare support. This has led to fears that MAID could be used as a tool to manage societal burdens rather than alleviate individual suffering.

The Nazi Comparison: A Step Too Far?

One of the most incendiary comparisons made by critics is likening Canada’s MAID program to Nazi-era euthanasia practices. Dr. Trouton vehemently rejects this analogy, calling it “terrible” and “unacceptable.” She emphasizes that MAID in Canada is voluntary, patient-driven, and carried out with compassion.

While the comparison is inflammatory, it serves to highlight the ethical concerns surrounding state-sanctioned death. Critics argue that once a society normalizes assisted dying, it risks devaluing life, particularly for marginalized groups.

The Expansion to Mental Health Patients

Starting March 2024, individuals with mental health conditions will be eligible for MAID. This expansion has sparked fierce debate. Supporters argue it provides relief for those suffering from chronic, treatment-resistant mental illnesses. Critics, however, worry that it could send a dangerous message—that society is giving up on helping people overcome mental health challenges.

Ethical Dilemma

The inclusion of mental health raises questions about capacity and consent. Can someone suffering from severe depression or anxiety make a rational decision about ending their life? Critics argue that the answer is often no, and expanding MAID to this group risks exploiting their vulnerability.

Cultural and Religious Perspectives

As a Christian African immigrant, I view life as sacred. The expansion of MAID raises profound ethical questions. In many African cultures, life is valued, and suffering is often seen as a part of the human experience that can lead to personal growth and spiritual strength. The idea of assisted dying conflicts with these values.

From a Christian perspective, life is a gift from God. The commandment “Thou shalt not kill” is clear. While compassion is essential, ending a life—even to alleviate suffering—raises serious moral concerns. We must ask ourselves: Are we playing God by deciding when a life should end?

A Society at a Crossroads

Canada stands at a moral crossroads. The expansion of MAID forces us to confront difficult questions:

- How do we balance compassion with ethical boundaries?

- Are we offering death as a solution to societal failures, such as inadequate mental health care or housing?

- What message are we sending to future generations about the value of life?

Proponents argue that MAID offers dignity and autonomy. Critics fear it’s a step toward dehumanization and cost-saving measures that prioritize economics over ethics.

A Slippery Slope or a Compassionate Choice?

The debate over MAID is far from over. It forces us to grapple with the most profound ethical questions about life and death. While proponents see it as a humane way to alleviate suffering, critics warn of a slippery slope toward devaluing human life.

As a society, we must ask ourselves: Are we addressing the root causes of suffering, or are we offering death as a convenient solution? Compassion or empathy must not cloud our judgment to the point where we lose sight of the inherent value of every human life. We must tread carefully to ensure that dignity in death does not come at the cost of dignity in life.